This winter, Foster Farms announced that a strain of avian flu was discovered at one of its commercial turkey ranches. While this strain of avian flu is not harmful to humans, it required the ranch’s animals be quarantined and killed to prevent the virus from spreading.

Biosecurity, preventing animals from sickness, is an essential component of pre-harvest interventions, and all processors are reviewing safety measures.

Since this winter, 15 states have confirmed cases of avian influenza, affecting more than 33 million birds, reported the New York Times. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) has confirmed that 100-thousand to several million birds qualify to be put down every few days. Once the flu affects one bird at a facility, the entire flock must be killed or the flu will basically do the job within 48 hours.

“Poultry processors are looking closer at vaccinations for specific virus strains in lots to improve biosecurity,” says James Dickson, Ph.D., a professor at Iowa State University, in Ames, Iowa. “A lot of folks are watching to see if increased biosecurity will also reduce Salmonella from their environment.”

The beef industry has vaccinations available for E. coli O157 but they are not widely used, he says, because producers and processors are not in agreement as to who should pay for them.

“At some point, the industry will need to come together and make it work,” Dickson says. “I hope it won’t take a biosecurity contamination to force an equitable solution.”

It is also hard for processors to add costs when beef prices are historically high, as well, he adds.

“Vaccines are being developed that target the mechanism of the infection, rather than the bacteria itself, which is more successful,” says Alejandro Castillo, Ph.D., associate professor at Texas AgriLife Research, Department of Animal Science, Texas A&M University, in College Station, Texas.

If processors use vaccines, they are preventing pathogen colonization within their animals, so they are immune to microorganisms or infections, he says.

Removing pathogens

Generally, there are three strategies for processors to remove pathogens from animals before slaughter, which reduces the risk of the product being contaminated: reduce pathogens in the environment, prevent colonization and add antimicrobials to feed or animals, Castillo says.

“The results seen don’t show one approach has an advantage over the other,” he says.

Evidence supports using probiotics (live microorganisms that can benefit the host) and antimicrobials (suppress growth of pathogens) to prevent foodborne diseases such as E. coli O157, says Guy Loneragan, Ph.D., professor of epidemiology and animal health, Department of Animal and Food Sciences, Texas Tech University, in Lubbock, Texas.

“More and more companies are manufacturing and using direct-fed microbials,” he says. “Many of which have showed efficacy against various bacterial pathogens.”

Direct-fed microbials (DFM) are live microbes used in animal feeds to produce antimicrobial compounds, prevent pathogens from colonizing the digestive tract and stimulate natural bacteria and the immune system, according to Loneragan and Mindy Brashears’ “Reduction of E. coli O157:H7 in cattle using Direct-Fed Microbials” presentation.

Plants have meaningful and incremental improvements in antimicrobials and carcass washes, Loneragan says.

“Also, we see renewed focus on personnel, their training and the resources they are given,” he says. “Most importantly, they have to understand their role in food safety, their task and how to improve over time.”

Employing viruses

Bacteriophages or viruses will actually kill bacteria, Castillo says.

Although they have been around for nearly a century, they are of interest to processors and scientists again because they are a viable alternative to the widespread use of antibiotics to prevent disease outbreaks at farms, which has been linked to the increase in antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

Accordingly, various university programs, such as Texas A&M’s, are developing mixtures of phages that will release pathogens to the cattle’s environment and feedlot to reduce colonization, Castillo says.

So far, only a few phages are available for commercial applications, because researchers are still learning about how their underlying mechanisms work. What they have discovered is they work best when targeting individual parts of infections, such as the skin or within organs, according to The Scientist magazine. (Editor’s Note: You can read more about bacteriophages on page 72 of this issue.)

Cleaning the carcass

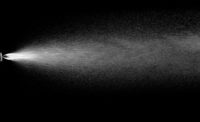

Cleaning the carcass before slaughter is another preventive measure, because bacteria can still contaminate the carcass even after it has been dressed. Several interventions exist to clean the carcass during and after the dressing procedure, such as trimming, steam vacuuming, carcass washing, hot water rinses, organic acid rinses and steam pasteurization. Dry chilling and refrigerated storage also help combat bacteria.

Many processors are using peroxyacetic acid-based, food-grade microbiocides, Dickson says.

“They are seen as a more cost-effective option than lactic acid, which works well but can be pricey per animal,” Dickson says.

For the past five years, lactic acid sprays have been successfully applied to beef carcasses, particularly when used during pre-chill and post-chill treatments, says Castillo.

Pathogen counts were lower in ground beef that had been produced with pre-chill and post-chill acid sprays than those that only received a post-chill spray, noted Castillo’s team’s “Lactic acid sprays reduce bacterial pathogens on cold beef carcass surfaces and in subsequently produced ground beef” paper for the Journal of Food Protection.

Steam pasteurization is generally not used as much as other methods anymore, Dickson says. In fact, a paper for the Canadian Journal of Veterinary Research, “Effectiveness of steam pasteurization in controlling microbiological hazards of cull cow carcasses in a commercial plant,” noted steam pasteurization was an effective means of improving beef carcass safety, but also indirectly contributed to the growth of some pathogenic microorganisms.

Using all resources

According to Dickson, processors are open to reviewing new pre-harvest technology claims, but the products need to prove they work as well as or better than (and as affordably) their current intervention methods.

“I would say the industry is skeptical, however, of marketing claims,” he says.

And the more the industry studies pre-harvest interventions — especially now during the avian flu outbreak — the more processors can learn where new challenges and opportunities exist, he says.

“There probably won’t be major breakthroughs with interventions, but we will learn more about adopting several technologies at once to fight pathogens,” Dickson says.