Home » foodborne illnesses

Articles Tagged with ''foodborne illnesses''

Tech | Processing

Tailor-made inventions for food safety

A multi-hurdle approach to pre-harvest interventions can be uniquely designed to meet each operation’s needs.

Read More

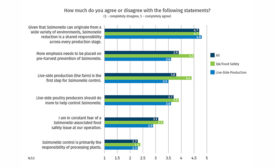

2020 Food Safety Report | Supplier's Perspective | Poultry

The state of Salmonella interventions in poultry

Read More2020 Food Safety Report | Science & Technology

The chemistry of peracetic acid

March 9, 2020

2020 Food Safety Report | Consultants Corner

Many small victories = 1 safe supply chain

The food-safety system in the U.S. works, if companies use the tools and innovations properly to protect consumers … and themselves.

Read More

Stay ahead of the curve. Unlock a dose of cutting-edge insights.

Receive our premium content directly to your inbox.

SIGN-UP TODAYCopyright ©2024. All Rights Reserved BNP Media.

Design, CMS, Hosting & Web Development :: ePublishing