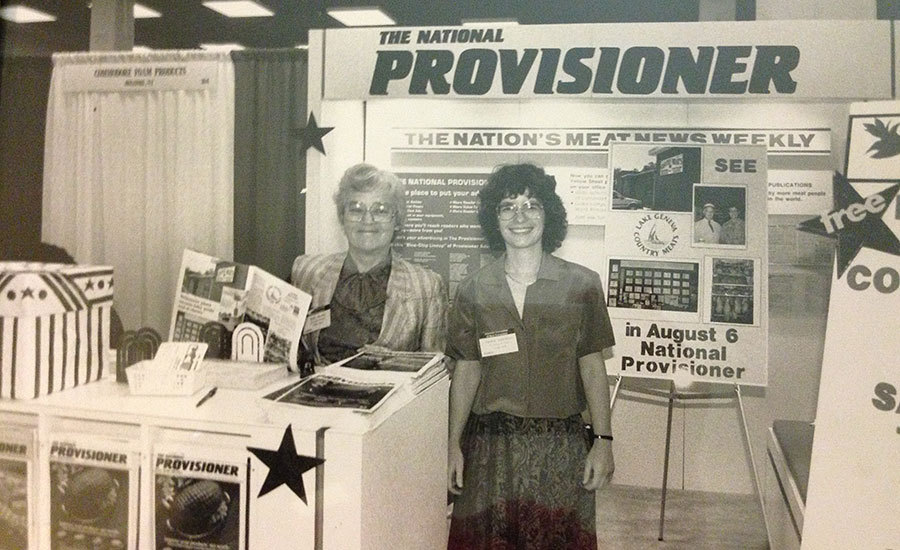

As someone with decades of experience on several trade magazines, including five years with The National Provisioner early in my career, I can attest to my mother’s genuine love of the meat industry. It’s not uncommon for trade magazine editors to become close friends with their colleagues in the office — as my mom was with her mentor, Ed Swem; Lester Norton; and Greg Pietraszek, for example — but Betty Stevens also developed strong relationships with her many friends in the industry. Indeed, nearly 10 years after her retirement, she still exchanged holiday card notes with a number of them.

My mom worked for The National Provisioner for 37 years and traveled to industry events around the country a half a dozen or so times a year during much of her tenure. I had the opportunity to accompany her on many business trips while growing up. The first was in New York City in 1964, at the same time as the New York World’s Fair. I was 5 years old then, so what I remember most was seeing a gigantic Ferris wheel in the shape of a tire. I don’t recall what event my mom was covering, but I do remember people being friendly with her, greeting her warmly in the hotel. A woman whose name I don’t recollect went with us to the fairgrounds.

I have more vivid recollections of attending American Meat Institute conferences with my mom on two or three occasions (perhaps even more) at the Americana Hotel in Bal Harbour, Fla. I was old enough (at least 9, I think) to be more independent then and would hang out by the wonderful huge pool (it had a high dive!) with some of the spouses while my mom covered meetings. I have particularly fond memories of Donna Bierman, a very friendly, fun woman who was the wife of Glenn Bierman, an industry leader. What struck me was that my mom had all of these friends she trusted to look out for her only child, while so many people chatted socially with her. Like many writers and editors, my mom was an introvert, but she truly relished the conviviality of meat industry conferences and conventions.

When I was a bit older, I went to the Western States Meat Packers Association convention in San Francisco twice with my mom and explored the city with Lynn Gallagher, the wife of one of her close NP co-workers, Tim Gallagher. I remember later my mom’s admiration for Rosemary Mucklow, who ran the association and was one of the few female leaders in the meat packing industry at the time. (Years later, in the Feb. 26, 1990, issue of NP, I would profile another woman my mother admired in the industry: Dr. Temple Grandin.)

As the de facto lead editor of The National Provisioner after the death of Ed Swem in the early 1960s (my mom functioned as the chief editor long before asking for and receiving a promotion in title), Betty Stevens similarly impressed people with her knowledge of — and passion for — the meat industry.

She also inspired other women in the field. For instance, after my mom died in May 2001, Fran Altman, who worked for Teepak for many years, shared with me that Betty Stevens was one of her mentors. (I had written to Fran about my mom’s death after receiving a holiday card addressed to my mother that December.)

|

Click here for more exclusive 125th anniversary coverage! |

Penchant for photojournalism, news

My mom was also known for always carrying a camera at industry events. As a kid, I remember seeing her with a succession of progressively smaller, professional-looking cameras — a Mamiyaflex, a Speed Graphic, and ultimately a 35-mm film camera, the latter being a lot easier to carry but not as high-quality as its forerunners, in her opinion. But I didn’t really appreciate her penchant for photojournalism until I joined NP’s editorial staff in the early 1980s as an assistant editor.

At every convention, my mom insisted that junior editors photograph people at each exhibit booth and take multiple photos at social functions, as well as during educational sessions. She was doing the same. No one could keep up with her!

Then a weekly magazine with many pages to fill, The National Provisioner also ran numerous photos of award recipients; I remember how meticulous my mom was about spelling each person’s name correctly in captions. Decades before the Internet, smartphones and social media, Betty Stevens recognized how thrilling it was for the meat industry’s movers and shakers to have their photos published in their field’s foremost national publication.

But my mom’s even greater passion was industry news. She believed staying on top of the meat and poultry industry’s ever-intensifying regulatory activity was her most important editorial responsibility. I remember seeing hundreds of issues of the Federal Register, the Congressional Record and many other publications and sundry papers sprawled across her large desk and piled on every flat-ish surface (including the floor, windowsill and radiator) in her office at work. (Among her co-workers at 15 W. Huron in Chicago, Betty was famous for her messy office, as well as her sharp mind.)

Although she was a strong writer, and painstaking editor and fact-checker, my mom’s journalistic passion was reporting. She would immerse herself fully in whatever she was covering, whether the Wholesome Meat Act of 1967 or the formation of the Food Safety and Quality Service (the precursor to the Food Safety and Inspection Service) 10 years later. Her education prepared her well for these challenges. Not only did Betty Stevens have journalism degrees from Indiana University and Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism, but also she honed her craft at the City News Bureau of Chicago (the legendary news agency that inspired the 1931 classic film “The Front Page”). On top of that, soon after joining The National Provisioner in the early mid-1950s, she decided to go to law school at night at DePaul University in Chicago to better understand the meat industry’s regulatory arena. (She was pregnant with me when she took — and passed — the bar exam.)

While her “News and Views” column usually included more news than opinion, Betty Stevens was quick to speak out against unfair maligning of the meat and poultry industry. If she were alive today, I’m sure she would say that the food industry in general has been too quick to capitulate to public misconceptions. As a lawyer, she cared more about evidence than marketing opportunities.

Last days at work

In the late 1980s, The National Provisioner — the closely held parent company of NP, the “Yellow Sheet” and the “Green Sheet” — decided to hire a management consulting firm essentially, as it turned out, to prepare the company’s assets for sale. A significant part of this process involved redesigning The National Provisioner magazine. Because the top three editors — Betty Stevens, Carl Swinehart and Greg Pietraszek — together had around 110 years of experience on NP, some people believed the magazine had an old-fashioned look and dated priorities.

My mom found the magazine redesign process annoying and frustrating from the beginning. (I witnessed this first-hand as an associate editor on NP, in my second stint with the company.) She considered the decision to change the publication’s frequency from weekly to “fortnightly” especially absurd. Individuals in the meat industry needed access to news when they could still act on it, she insisted. She didn’t mind the addition of color to the black-and-white magazine, but she disliked many other changes made to the publication.

A vice president, as well as the editor-in-chief, at the end of her full-time tenure with the firm, Betty Stevens had earned the owners’ respect. However, she butted heads too many times with the consultants and certain managers, and ultimately lost her position. (A number of other employees with decades of seniority left The National Provisioner around that time as well.) After a brief time as a contract news writer under Chuck Cannon, who succeeded her as editor-in-chief in his third stint working for the magazine, Betty Stevens left The National Provisioner for good — before the magazine was sold to what was then called Stagnito Publishing Co.

My mom was only 68 years old at the time. Although she found new pursuits in retirement — most notably taking biology courses for credit at Harold Washington College in Chicago — I know she had hoped to remain with NP well into her 70s. She stayed in contact with her industry friends and former co-workers — and still followed meat and poultry news as an avid newspaper reader — until her death from cancer at age 78.

Be that as it may, my mom treasured her nearly four decades on The National Provisioner. A career woman since the 1940s — and a divorced single mom at that — she had no regrets about her choices.

I remember my mom working late at night at home — usually after we had gone out to dinner — first writing articles in longhand on a legal pad while sitting on her favorite easy chair, then pounding out final drafts with her trusted Royal manual typewriter. She inspired me in so many ways. I miss her dearly. NP